Coaching Kids Who Get Easily Frustrated

Coaching frustrated youth athletes can be tough—but with the right tools, it becomes one of the most rewarding parts of coaching. This blog shares practical strategies for helping kids manage frustration, reset quickly after mistakes, and build confidence and resilience in practices and games. Perfect for youth coaches and sports parents looking to improve emotional control, effort, and team culture.

2/17/20267 min read

Every coach knows this kid.

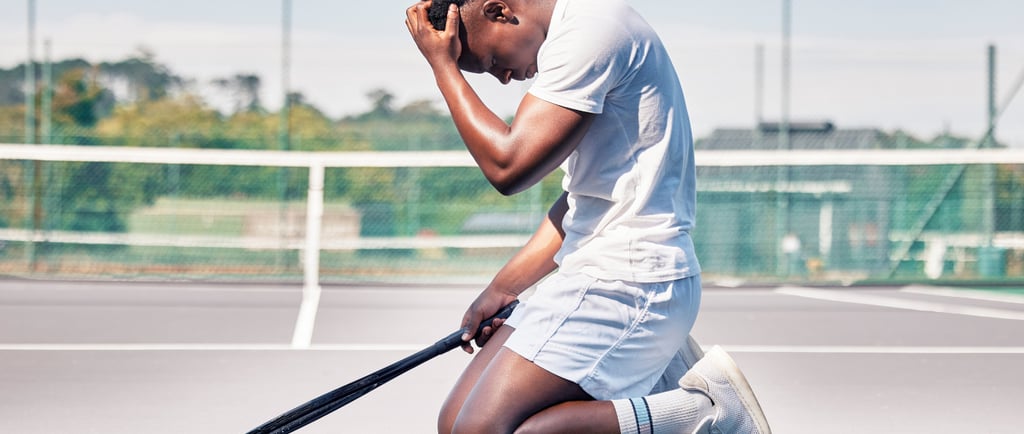

They miss a shot and their shoulders drop like somebody unplugged them. They boot a soccer ball and immediately start talking to themselves like they’re their own worst enemy. They strike out, throw the bat down, and you can almost feel the rest of the inning slipping away because now they’re not just playing the game—they’re fighting their emotions inside the game.

If you’ve got a player who gets easily frustrated, you’re not dealing with a “bad kid” or a “problem attitude.” Most of the time, you’re dealing with a young athlete whose feelings are bigger than their tools. They care. They want to do well. They hate messing up. And they haven’t learned how to recover quickly when things don’t go their way.

That’s why this matters: frustration isn’t just a moment. It can become a pattern. If it’s not coached, it spreads—into confidence, into effort, into teammate energy, into the entire culture of your practices and games. And on the bigger picture, it impacts whether kids stay in sports at all. A frequently cited review in sports medicine literature reports that 30% of youth say negative actions by coaches and parents are a reason they quit sports. That’s not saying frustration is the whole story, but it’s a reminder that the environment we create—and how we respond to kids when they’re struggling—can shape whether sport feels like a place of growth or a place of shame.

So let’s talk about what actually helps, in real coaching terms. Not “just toughen up.” Not “calm down.” But concrete, repeatable coaching strategies that help athletes regulate, reset, and compete with confidence.

Why frustration shows up so fast in youth sports

Frustration is usually a collision between high expectations and low emotional skill. Young athletes often experience mistakes as something bigger than a missed shot or a dropped catch. In their mind, that moment can quickly become: “I’m bad,” or “I’m letting everyone down,” or “Coach is going to be mad,” or “My parents are going to be disappointed.”

The younger the athlete, the more likely their brain treats mistakes as danger instead of information. Add a loud environment, other kids reacting, adults watching, the pressure of winning, and maybe a teammate rolling their eyes—and that emotional reaction spikes even faster. Many kids don’t have a “reset button” yet. They only know two settings: hold it in until it erupts, or explode immediately.

This is where the research around emotion regulation matters—not as academic theory, but as a practical coaching reminder. Studies of athletes (including young athletes) have found that different emotion regulation strategies relate differently to mental health and performance experience—particularly cognitive reappraisal (reframing the situation) versus expressive suppression (bottling it up). In plain language: helping kids learn to reinterpret mistakes and move forward tends to be healthier than teaching them to “stuff it” or pretend they don’t feel anything.

And that’s the key coaching shift: you’re not trying to eliminate frustration. You’re trying to shorten it.

The coaching goal: teach a faster recovery, not a perfect emotional life

Frustration is normal. Competitive kids get frustrated. Kids who care get frustrated. Kids who are learning something hard get frustrated. The problem isn’t the emotion—it’s the spiral.

A spiral looks like this: mistake → emotional reaction → loss of focus → second mistake → bigger emotion → withdrawal or outburst → more mistakes or disengagement. Once you see it that way, your coaching becomes clearer. You’re not coaching “attitude.” You’re coaching interruption. You’re teaching the athlete how to catch the spiral early.

And here’s something that’s easy to forget: the athlete often knows they’re overreacting, but they can’t stop it. That’s why “stop doing that” rarely works. They need a script. They need a routine. They need a different path their brain can follow when their feelings surge.

What great coaches do differently with frustrated players

Great coaches don’t get pulled into the athlete’s emotion. They don’t match intensity with intensity. They become the thermostat, not the thermometer. They keep the moment small. They give the athlete a simple next step. And they build a team culture where mistakes don’t equal embarrassment.

That starts with how you respond in the moment.

When a kid melts down after a mistake, your first job is not correction. Your first job is connection—briefly. Not a long therapy session, not a speech, not extra attention that rewards the behavior. Just a short, calm acknowledgment that keeps the athlete from feeling alone in the emotion. Something like: “Yep. That one stung. I get it.” The goal is to de-escalate the nervous system, not to debate the mistake.

Then you move into direction: “Reset. Next play.” The shorter and more consistent this is, the better. Frustrated athletes often lose cognitive bandwidth. They literally can’t process three coaching points and a life lesson in the heat of the moment. They need one cue and one action.

This is where coaches can make a huge difference by teaching a reset routine ahead of time and using it consistently. The routine doesn’t have to be complicated. It just has to be repeatable under pressure. A simple version might look like this: one slow breath, shoulders down, eyes up, one phrase—“next play.” The specific routine matters less than the fact that it’s practiced and predictable.

You’re building a mental habit the athlete can lean on when they feel flooded.

The “job” tactic: the fastest way to break a spiral

One of the most effective tools with frustrated players is giving them a job immediately after a mistake. Frustration thrives in stillness. The athlete gets stuck replaying what happened. A job creates action, and action creates control.

Instead of saying, “Don’t get frustrated,” you give them something to do that moves them forward: “Sprint back and talk on defense.” “Go set your feet and be ready for the next pass.” “On this rep, focus only on your follow-through.” It’s not punishment. It’s redirecting energy into something productive.

Kids who get frustrated often feel like they’ve lost control of the situation. A job gives them control back in a healthy way.

How you correct matters more than how much you correct

Frustrated athletes often interpret correction as confirmation: “See, I am bad.” So when you coach them, keep feedback small and specific. Think of your correction like a Post-it note, not a full page.

You can still be honest. You can still hold standards. But you deliver it in a way that doesn’t pile on. If you need to correct a technical mistake, anchor it to something they did right first: “I love your hustle. Next time, get wide before you catch.” That one sentence is more coachable than a long lecture that the athlete won’t remember.

This is also where growth mindset language helps in a real, practical way. Growth mindset isn’t a motivational poster—it’s the difference between “mistakes mean I’m failing” and “mistakes are part of improvement.” A 2025 paper discussing growth mindset in sport links it with things like improved recovery after competitive failures and persistence through challenge (citing prior research). For youth coaches, that translates to a simple habit: praise the response and the effort to adjust, not just the outcome.

When a kid is frustrated, the most powerful compliment isn’t “nice shot.” It’s “that was a great reset.”

Build a culture where the team doesn’t punish mistakes

Here’s where frustration becomes a team issue instead of an individual issue: teammate reactions.

If kids roll their eyes, groan, blame, or sigh when someone messes up, you’re creating a social threat environment. And kids who are already prone to frustration will struggle even more. They’ll rush, tighten up, and react emotionally because they’re anticipating judgment.

So part of coaching frustration is setting clear team standards for body language and responses. You don’t need a long list of rules. You need a consistent message: we don’t embarrass teammates. We don’t perform disappointment. We don’t dogpile mistakes. We reset and move forward.

This is where you, as the coach, have to model it too. If your face shows disgust at mistakes, if your tone gets sharp, if you throw your hands up, your athletes learn that mistakes are dangerous. If you stay steady, they learn the opposite: mistakes are manageable.

Don’t ignore the adults: parent behavior can amplify frustration

A lot of youth sports frustration is fueled by adult energy. When parents coach from the sideline, react dramatically, argue calls, or put pressure on outcomes, some kids absorb that stress and carry it into every rep.

This isn’t just your imagination. A Liberty Mutual survey on sportsmanship in youth sports reported that 55% of coaches experienced parents yelling negatively at officials or their own kids, and it also notes other forms of negative sideline behavior. Separately, the National Association of Sports Officials’ “Sporting Behavior” survey reports that roughly 40% of officials believe parents cause the most problems with sportsmanship. And a recent ESPN write-up referencing that NASO survey highlights that more than 40% of respondents cited unruly parents as the biggest impediment to job satisfaction.

You can’t control every adult, but you can set expectations. A short preseason message that encourages parents to praise effort, composure, and “next play” responses—rather than outcomes—will help. The goal isn’t to police parents. It’s to create alignment so the athlete isn’t getting two conflicting coaching systems: one calm and process-focused, one loud and results-focused.

The bottom line: you’re coaching a life skill disguised as a sport skill

When you coach a frustrated player well, you’re doing more than protecting your practice flow or saving a game from a meltdown. You’re teaching a child how to handle adversity while other people are watching—a skill they’ll use in school, friendships, jobs, and life.

And the most important thing to remember is this: frustrated athletes don’t need a coach who’s softer or harsher. They need a coach who’s clearer. Clear expectations. Clear routines. Clear standards for response. Calm tone. Quick reset. Back to play.

If you can consistently teach a frustrated kid how to shrink the space between “mistake” and “next play,” you’re giving them something priceless: the ability to stay in the fight without fighting themselves.